Douglas Hartree and LEO (from Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Douglas_Hartree)

Hartree’s fourth and final major contribution to British computing started in early

1947 when the catering firm of J. Lyons & Co. in London heard of the ENIAC and sent a

small team in the summer of that year to study what was happening in the USA, because

they felt that these new computers might be of assistance in the huge amount of

administrative and accounting work which the firm had to do. The team met with Col.

Herman Goldstine at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton who wrote to Hartree

telling him of their search. As soon as he received this letter, Hartree wrote and invited

representatives of Lyons to come to Cambridge for a meeting with him and Wilkes. This

led to the development of a commercial version of EDSAC developed by Lyons, called

LEO, the first computer used for commercial business applications. After Hartree’s death,

the headquarters of LEO Computers was renamed Hartree House. This illustrates the

extent to which Lyons felt that Hartree had contributed to their new venture.

Hartree’s last famous contribution to computing was an estimate in 1950 of the

potential demand for computers, which was much lower than turned out to be the case:

“We have a computer here in Cambridge, one in Manchester and one at the [NPL]. I

suppose there ought to be one in Scotland, but that’s about all.” Such underestimates of

the number of computers that would be required were common at the time!

Presentation Friday 26 April, 2024 at 17.00 BST by Andrew Herbert on the EDSAC Rebuild at TNMoC. A recording is available here Zoom Recording.

Andrew commented the following in the abstract.

While EDSAC can justifiably claim to have been ‘the world’s first practical digital electronic stored program computer’, as is well-known to the LEO community, Pinkerton, Lenaerts and colleagues had to address many of the ‘inadequacies’ to produce in LEO a robust machine that could take on the information processing needs of the Lyons company and be the world’s first successful business computer.

Andrew Herbert: The EDSAC Rebuild at TNMoC Read More »

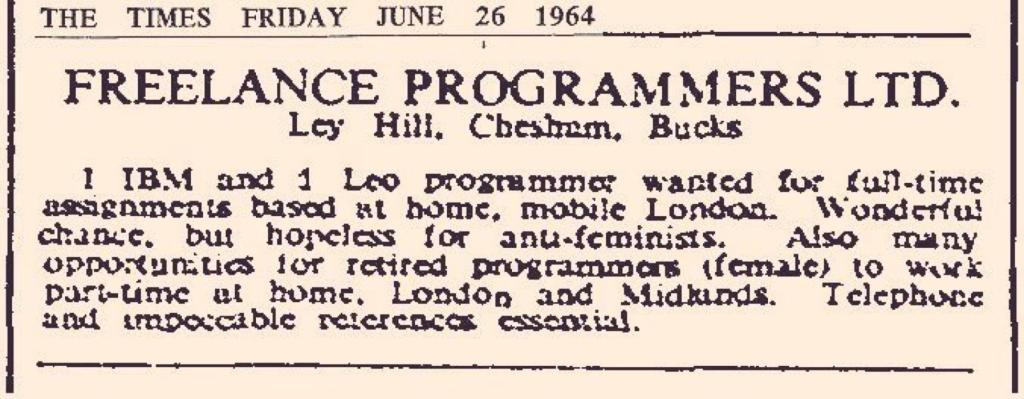

In 1964 the inimitable Dame Stephanie ran this advert in The Times, seeking programmers for her startup. “Ant-feminists need not apply”-plus opportunities for women who’d retired

Marie Hicks Twitter Message: Read More »

Denis Hitchens. Operator on LEO III/15 at Shell Australia

Neil Lamming interviewed me and conducted the aptitude test. But the person I was

really trying to dredge from my memory was Bill Cheek who along with Jack Dankert

encouraged me to return to full-time study. I was 19 and 20 at the time, turning 21 about

a fortnight before I went to RMIT — imagine a 20 year old shift leader with the fate of

SCO in his hands!! So for me as a whippersnapper training 35+ year olds was a life

defining experience and one which a bit later in life when I was President of the Students’

Representative Council (elected leader of some 12,000 students) I was able to refer to

when addressing Melbourne Rotary ( yes, all the big wigs). A fuller version of the

reminiscences are available in the LEO Dropbox archive at

https://www.dropbox.com/s/bqgrbhxh9cp4s4k/Denis%20Hitchens%20Reminiscences.docx?dl=0

Brian Hobson: I am glad that you, (Hilary Caminer), were able to attend our recent

“LEO do” as chaotic as it was! You asked if I would explain the origins of our group and

also to help you understand our Lyons/LEO relationship as it seemed rather confusing.

I will do my best. The meeting started when Norman Beasley retired from Lyons

in/around 1982. Norman had been a member of Lyons/Leo from the early days and was

Operations manager on LEO 1, LEO II/1, and LEO III/7 before becoming Computer

Consultant to the Lyons group of companies.

Norman lived in Chalfont St Giles (I think this is correct) and Peter Bird (Lyons

Programming Manager) and Alex Tepper (Lyons Operations manager) would go to visit

him fairly frequently. Carol Hurst, who was at our meeting, also lived nearby and had

also left Lyons would join the others making a foursome. In my Lyons career I started in

Operations as an operator (employed by Norman) and later became a consultant working

with Norman. When Alex Tepper was promoted to Head of Computing for Lyons I

became Operations manager and joined the gathering.

All Lyons computer staff are quite a close knit group and various members moved into

senior positions within other companies within the group as Accountants or Head of

Computing, etc. Tony Thompson, who you met, became Chief Accountant for various

companies, Alan King (now passed away) became head of Lyons Maid computing. They

joined in our meetings and gradually as time went on our group has continued but with

varying members, as old ones passed away others came to know of us and joined. Peter

Bird was the mainstay organiser as he had the most contacts. Cyril Lanch is a fairly

newcomer to our group but did not step back quick enough when volunteers were sought

to carry on Peter’s organising! Hopefully that explains our group, now for the

LEO/Lyons feelings – difficult!

History of Lyons and computers. Lyons built a computer to do work for Lyons Electronic

Office (LEO), staff working on the computers were Lyons staff. With the success of

computers Lyons formed a computer company LEO Computers Ltd but the staff although

working for LEO were still Lyons staff at heart. When the company LEO was sold the

computers remained at Lyons and were operated by Leo staff until they chose to remain

at Lyons or were replaced by new Lyons staff.

Lyons computer history goes from LEO I through Leo II/1, LEO III/7, LEO 326/46 and

eventually to IBM computers. Our attachment to LEO may be explained by the fact that

the original computers were still in use at Lyons long after LEO had been sold and in

many instances the staff working them were the original staff. When LEO was sold the

computer department became LEO and METHODS, then Lyons Computer Services Ltd

(LCS My best analogy would be: If you had a daughter and she got married she would

still be your daughter and a member of your family although she would have joined

another family, you would continue to be proud of her. The same is how our computer

department feel.

When LEO was sold the computer department became LEO and METHODS, then Lyons

Computer Services Ltd (LCS), and finally Lyons Information Systems Ltd (LIS).

As you may now gather we were very proud of our heritage but so was the computer

industry. We as a Computer Bureau (which we had been from day 1 of computers)

strived to continue to be at the forefront of computer usage and computer and peripheral

manufacturers were very keen to be associated with us offering us very competitive deals

to use their equipment. Our computer department was frequently put under the

microscope by the main Lyons Board as the newer family Board members felt that

computing was expensive but on every occasion the auditing companies, including IBM,

were in awe as to how we are able to do so much with so little and still lead the

world. An example of this was back when Lyons had a fire on the Xeronic Printer in the

LEO III/7 computer room. We made an arrangement with the Post Office (as it was then)

to use their LEO III (overnight) in Charles House which was just across the road from

us. Our shift of 6 operators replaced a shift of 20+ operators.

I cannot remember the trade magazine that did a piece on us as we were the first company

to wire an entire building with various departments on different floors to use Local Area

Networks linked into the mainframe. Also, one of our external customers was a large

American personal tax company which had a large computer centre in the States but

wanted a worldwide centre based in London. We installed a duplicate of their system

onto our computer, they provided no computing staff as all maintenance etc. would be

done from the States we only had two user/managers with us. Their system was difficult

for their users to manage and I spent a lot of time supporting them because of the

complexity of their system.

Eventually I volunteered to improve it for them and wrote a few simple programs

and restructured their system making it much more efficient (saving hours a day of

machine and their input time). The computer staff in America were interested in what I

had done and came over to see for themselves, they were amazed and the CEO asked

permission to adopt our version of their system to replace their own!

My own involvement with Lyons started while I was at school. My brother, Colin, whom

you met was an operator at Lyons on LEO II/1 (but employed by LEO Computers) and I

used to go with him to work some evenings or when I was not at school. I was able to

help operate the LEO II computer (unofficially of course) and met the engineers on the

LEO III/7. When Colin moved to Hartree House I also used to go there as well and

helped out on the LEO III installed there. I loved the job and it really appealed to me so

when I left school (in 1966) I went for interviews at Lyons and ICT (as it was

then). Norman interviewed me and offered me the job (it helped that I knew several of

the staff by name which impressed him!). I worked my way up from trainee operator to

Ops Manager until the closure of the company in 1991. I won’t bore you with my life

history of the roles I held and of the changes in company structure that I made over the

years as most of this was during our IBM period.

I hope that this gives you some insight into our little group and our attachment to LEO

and why we feel a little side-lined when at the LEO Computer Society gatherings Lyons

seems to be irrelevant. Maybe that is changing now but at the few meetings I went to

over the years that is how it seemed which is why I have never bothered joining

Colin Hobson: Weather, Wildlife and LEO Computers

Both LEO 1 and the LEO 2s were not installed in cosy, air-conditioned palaces. They went

into normal office accommodation and the heat, generated by the hundreds of thermionic

valves was conducted away by fans and overhead ducting. The operators were kept cool

only if they could open the office windows! This could cause a number of unexpected

problems:

On LEO 1 rain could be a problem. It was necessary to look outside before turning

anything on. If it was raining, or snowing, the heaters in the valves needed to be turned on

before the cooling fans. This built up enough heat to ensure that the water droplets sucked

in were vaporised before they hit a hot glass valve cover. Failure to do it this way round

would result in a series of high pitched squeaks as the glass, of the valves cracked. This

would be followed by the sound of engineers swearing! If there was no rain, it was better

to get the cooling up and running first.

On LEO 2 this was not a problem. The ventilation system didn’t cause the computer much

in the way of problems. The computer did provide a lot of heat, most of which was

conducted away by the ventilation system. However, there was still a lot of peripheral

equipment and human bodies churning out heat. The only option, certainly on LEO 2/1 was

to open the windows to the outside world. Mostly this worked well. However, there were

times when the outside world made its way into the operating area to cause chaos. Wildlife

was one such problem. The occasional visiting bird could provide some distracting

entertainment but the worst problem I can remember was a swarm of small insects which

came in through the open windows and settled on the paper tapes and punched cards. They

got squished into the holes in the cards and tapes changing the data.

Many years later I was working at a Post Office (now BT) site where a snake made its way

through one of the doors from the outside world, down a short corridor and then got stuck

between the automatic airlock doors into the air-conditioned computer hall.

Colin Hobson adds I was worked on LEO 1 and subsequent machines but am not sure

about recordings. LEO 1 certainly did make a noise but I have a vague recollection that

the speaker was not in the original hardware but in the dexion operators console, which

was a later addition.

LEO 1 was on a platform at one end of the room (hall). There was an engineer’s console

up there which the operators did not use. The dexion operators console was down on the

parquet flooring along with all the peripherals. The peripherals were aligned in two rows

with shallow metal cable runs going back to the main frame platform. The room was not

air conditioned and at times it was necessary to open several windows to allow the

operators to breathe! A warm wet day was a real problem as we had to make sure the

heat in the room was enough to evaporate the rain before we could open the

windows! Another side effect, on the operators, was the smell of cooking which often

wafted up from below!

Note: Colin Hobson was interviewed by Marie Hicks for her book Programmed

Inequality (see above) and provides one of her case studies noting the story of LEO

David Holdsworth – I went to state schools in the then West Riding of Yorkshire, where the Director of Education was Alec Clegg, well-known for his left-wing views. As a result, I left a co-ed comprehensive school in 1961 and went on to read Physics at Oxford University following a few months working in the works laboratory of English Electric. I began my computing career as a physics research student writing Algol60 programs modelling quarks on a KDF9. After discovering that I might be better at computing than physics, I got a job at Leeds University in 1967 where we implemented the Eldon2 multi-access operating system on KDF9, which was still running at NPL in 1980. Leeds University’s KDF9 was succeeded by an ICL 1906A where I was involved with George3 and George4. At Leeds I was an early champion of Amdahl and of UNIX.

I was often helping others with their computing issues. After completing the doctorate, I went to a job in the Electronic Computing Laboratory at Leeds University, where I worked in a variety of roles until 2004. Actually the thesis was written up while at Leeds. My developments on their KDF9 are documented in Resurrection, the journal of the Computer Conservation Society. Suffice to say that I was a key figure in implementing the Eldon2 multi-access system, which enabled us to offer interactive computing from March 1968, with 32 tele-types connected via a PDP-8.

I started resurrecting/preserving software in the late 1990s. By resurrecting/preserving I mean getting the software into a modern digital state and providing the ability to execute it. George3 was the first such rebirth, using the official George3 issue magnetic tapes, followed by the BBC micro’s Domesday Project. The first software rescued from printer listings was KDF9’s Whetstone Algol. I was also involved in the preservation of digital material that is not computer software. An important principle of my work has been that emulation should work on a wide range of current hardware, with a view to working on future systems. Sometime around new year 2013, John Daines asked if I could use my skills in software resurrection on the pile of listings of Leo III Intercode that had been collected by Colin Tully. After resurrecting software for 1900, BBC micro and KDF9, I was keen to try rescuing software from a machine of which I had no prior knowledge, so as better to appreciate what we need to preserve if future generations can comprehend early machines. I was delighted when John Daines asked me if I could resurrect the Intercode system that he had obtained from Colin Tully’s widow. I immediately put my work on the Edinburgh IMP system on the back burner, where it resides to this day.

I came to Leo III expecting to find an assembly language and set about implementing Intercode treating the printout as the source text of an assembly language. It soon dawned on me that there were no labels, and that really I was dealing with a machine code for a fictitious machine, a sort of Leo IV.

The raw machine code also came as something of a surprise, devoting all sorts of complexities to computing with a variable radix, and using sign-and-modulus for information in the store but converting to 2’s complement in the A register (but not the B register). A step-by-step account of my voyage of discovery which led to a working Leo III emulation is here.

I am fascinated by Intercode, as I think it may offer a window onto the time when assembly languages were emerging, a time before my own entry into computing, perhaps via a privileged side entrance. Seehttps://www.dropbox.com/s/g2ullpu7ooxwvya/David%20Holdsworth%20Memoir.docx?dl=0

Stan Holwill: My LEO Involvement & Memories January 2018 Date of birth 1932.

Abstract: Stan started his working life in 1947, with an interest in engineering, at an

electrical engineerg firm Clifford & Snell in Sutton Surrey.

I served a five years engineering apprenticeship. During this time I spent one day a week

at Wimbledon Technical College studying for ONC & HNC, followed by National

Service in the Royal Corp of Signals working as a radio mechanic. On return to civilian

life spotted an advertisement in Wireless World from J. Lyons for an engineer to work on

digital computers. Applied, interviewed by Ernest Lenaerts and Peter Mann, accepted

and joined LEO as junior computer engineer in January 1956, working at Cadby Hall on

LEO I. Rapidly promoted to prototype commissioning engineer on LEO II/I and then

chief maintenance engineer for the Elms House LEO II. From November 1956 acted as

managing commissioning engineer for LEO IIs until 1961 responsible for a series of

LEO II customers starting with Stewarts and Lloyds (LEO II/3) and going on to LEO

II/11. In 1963 appointed Manager of the Maintenance Development Department

(London). Remained in post until end 1970 when Minerva Road was

closed. Subsequently worked with other ICL machines until retirement in 1991

Enjoyed his 15 year career with LEO, with working with LEO II the highlight.

Text: https://www.dropbox.com/h

Alan Hooker memoir.

Alan Hooker’s reminiscences: here is what I remember of my time at LEO. Some of the dates

area bit vague and might be suspect but then that describes me now!

I’ve also included notes on my visit to New Zealand which you might find interesting. In 1963 it

was like pre-war Britain and that scenario has gone forever now.

I joined LEO in June 1958 at Elms House from the BBC and went through a six week LEO II

training course, at the end of which I was thoroughly confused and questioning whether I had

made another bad career choice. I was given a number of small maintenance jobs and utilities

to work on then assigned to some major changes to LEO I programs. As I remember they were

full of formed orders (Editor: orders created by the programmer by treating an instruction as if

it was data held in store) as there was no B-line modification and my program errors frequently

caused me to try to obey data. It was here that the penny dropped–the computer can try to

obey data or do arithmetic on instructions, in memory they are both the same. Even so the

Lyons bakeries were not brought a grinding halt and I emerged with the beginnings of

programming ability.I returned to LEO II work under Betty Cooper (Newman) to write the Lyons

Ice Cream suite. For Betty I had to code in ink and she checked of code. Any sheet of code she

disapproved of was returned to me for rewriting (in ink). By the time the code got to Data Prep

it was fit for testing. Another thing I remember about this suite was the correction to sales

commission due to fluctuations in ambient temperature between this year and the

corresponding temperature last year. I therefore was required to code a routine which, inter

alia calculated corrected sales as actual sales times a constant raised to the none integral power

of the difference between the temperatures calculated to one position of decimals. This could

be positive or negative. Whilst I was sitting there with furrowed brow John Lewis helpfully told

me to increase the temperatures by ten and divide the answer by 100. And so the calculations

were done and so the commission was calculated and the salesmen found it incomprehensible!

About this time Lector was introduced and the Xeronic printer installed in Elms House, so I

worked on modifying the Teashops system to accommodate them, In 1960 I was assigned to

help The Standard Triumph Motor Company (LE$O II/8) in Coventry develop their stock control

system under the management of Arthur Payman. Arthur had a Messerschmitt two seat/three

wheeled bubble car in which we trundled up the M1 every Monday morning, and I returned by

train at the end of the week. I think I worked on this project for about a year.

I then moved to Hartree House to work for Doug Comish on the Persian Lamb Sales System for

the Hudson’s Bay Company (Editor: a LEO II bureau job). This was the first time that I had acted

as the front man doing requirements, design, coding, testing and delivery. Added to that the

Powers Samas Samastronic printer was LEO’s first Alpha numeric printer and was a bit

whimsical in behaviour. It struck me as a bit odd that Persian Lambskins grown in South West

Africa should be auctioned in London by a company with a Canadian name. Very little went

according to plan. The sale was originally going to be small with plenty of time between receipt

of skins and the auction to sort out problems, and the manual system would be the backup. In

the event, because of the African weather, lambing was late, the closing date for the sale was

late and a quarter of a million skins had to be and processed. On the day of the sale, David

Caminer, and the engineer (who brought his French Horn and played Till Eulenspiegel for us)

and sundry volunteers worked through the night, sometimes with fingers in the dyke, and

delivered the results in the morning. What is more, despite the complexities of the accounting,

we balanced to the penny!

Shortly after this we did stock control and sales forecasting for Lightning Fasteners, a subsidiary

of ICI and the major source of zip fasteners in the UK. This was interesting because it was an

early commercial use of exponential smoothing of averages. Another stock control system we

did was for the H.J. Heinz company, a just-in-time raw commodity scheduling system for their

factory in Hayes. I don’t remember when LEO 3/1 was installed at Hartree House (Editor: 1967)

but I was then put in charge of a number of programmers working in Intercode and I also

lectured on the LEO 3 Programming Course .My manager was Helen Jackson (Clark). People in

the room I remember were Alan G Hooker, Jim Feeny, Tomas Maria Leonard Wizniewski,

Rosemary Oakeshott, Diana Myra Loy Cooper (Didy); others whose names I don’t today recall

but will probably remember tomorrow whilst forgetting these. I was then tasked with setting up

a unit to write standard commercial programs. We managed to design a flow chart for updating

serial files and a prototype data vet program, but the availability of random access discs and

IBM’s initiative with CICS took the wind out of those sails and efforts were diverted to standard

commercial routines.

I moved on to work for Ralph Land as a consultant, basically a Sales Support analyst. One

Monday he said to me “How would you like to do a project in New Zealand for a couple of

months?”. “When?” I asked.” “Next Friday” replied Ralph. So four days later with a suitcase,

passport and a round the world ticket I set off for Wellington, via Hong Kong and Sydney. I

arrived in Wellington late Monday afternoon, was met by David Howard, the local General

Manager and was driven straight to the office of English Electric Leo Computers to start work! A

good job I had broken the journey in Sydney. The computer bureau was based on an EE KDF6,

and offices were housed in a small square perhaps about half a mile from the harbour. I had

been booked into a small hotel a few minutes’ walk from the offices, on the face of it very

convenient, but in the event it turned out to be little different from a dingy boarding house with

nowhere to work in the evening. When I complained about this the next day, the excuse was

that there was large business convention in town and nothing better was available. I therefore

went to the best hotel in town, the Grand, and booked a room for a month. After that I

returned to the office to start preparing my Tender. The Company was hopelessly under

resourced to bid for a distributed banking system, or to support such a system if the bid was

successful, but I was there to have a go. At the end of a week I had overwhelmed the typing

resources (no word processors in those days). Then there was a break of a week while the

commercial and other local aspects of the proposal were prepared, during which I was sent

down to Christchurch in South Island to investigate the potential market for computer bureau

business. I made a few appointments, but I felt the time was not ripe for a start-up bureau

centre.

Returning to Wellington to submit the proposal to the Bank of New Zealand, I was offered the

post of General Manager of South Island with a view to taking over from David Howard as

Country Manager when his contract expired in a year’s time. Although tempted, I asked to

consider my answer after returning to the UK and assessing the future there. I also took the

opportunity to call in at the local office of Atlantic and Pacific Travel whose Managing Director

was the brother of Ian Crawford, a LEO consultant and one of my Kingston flatmates. They

kindly rerouted my return trip via Fiji, Tahiti, Los Angeles, San Francisco and New York,

returning to Wellington.

From Wellington I flew to Auckland to touch base with the local office of English Electric. I had

a great time in New Zealand but it was a technological backwater; looking back, I probably

made the right decision from a career point of view. Once back in the UK I found it difficult to

find a career niche so I left EELM to become the General Manager of Tyndall computers in

Bristol in (I think) April 1965. Apart from acting as Director of the ICL Computer Users

Conference, I had very little contact with ICL for the next few years. I joined Dataskil in 1979 as a

Project Manager in PMS Reading under Ollie Smith and John Benbo, largely in a support role for

other Project Managers and doing project Audits. One project I managed was to act as the

General Sales Manager for Dataskil under George McLeman. Acting as line management of

wheeler dealer salesmen and their was beyond my experience, and I was regarded with

suspicion by the unit. However with a £30 million sales target and a year to achieve it we had to

get on with it and we made the numbers. I Then returned to PMS. Several company

reorganisations later I was the manager of the unit but the culture had changed and I resigned

from the unit to manage the transition of the BAA data processing systems from Honeywell to

ICL computers. It was a five year project, the largest project I had managed and when I took it

over it was exactly two years behind schedule. Three years later we finished it on time and

budget! I then took early retirement.

A fuller account including recollections of travelling and holidays is included in:

https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/qjywskwpwzrnyn1t0lb2n/Alan-Hooker-memoir.doc?dl=0&rlkey=eecbdm3e0e5zydk5k4gkoyf29